Richard (Ricco) Mattessich passed away on Sunday, September 30, 2019. Ricco left an incredible impression on many of us here at UBC Sauder, and he will be deeply missed by all who knew him. Please visit his In Memoriam page here.

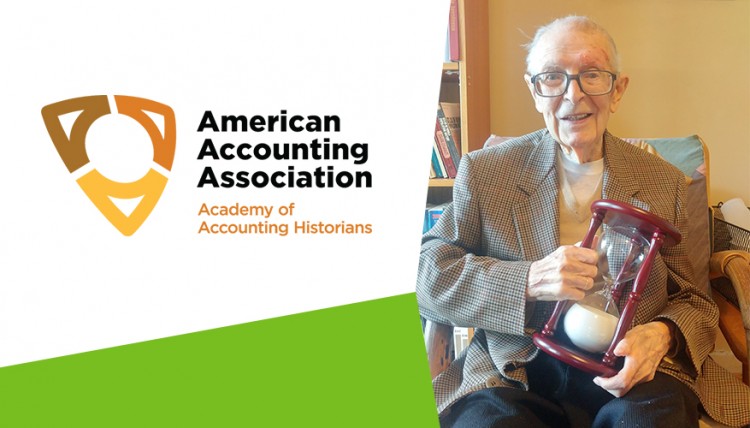

Richard Mattessich, Professor Emeritus, Accounting and Information Systems Division at UBC Sauder, has been honoured by the American Accounting Association’s Academy of Accounting Historians with the 2019 Hourglass Award for the second time in his career.

The award was presented at the American Accounting Association Annual Meeting in San Francisco, CA on August 11th, 2019. Mattessich, who recently celebrated his 97th birthday, was unable to attend the ceremony, so his friend and colleague Giuseppe Galassi, currently visiting UBC Sauder, was honoured to be asked by Mattessich to accept the award on his behalf.

The Hourglass Award is presented annually to an individual who has made a demonstrable and significant contribution to knowledge through research and publication in accounting history. It is the most significant research award offered by the Academy, and the second time Mattessich has been chosen to receive the award, the first time being in 2003.

Mattessich, who has authored over 25 books and over 180 papers published in books, anthologies and learned journals, is best known for introducing the concept of electronic spreadsheets into the field of business accounting in 1961, as well as pioneering analytical and philosophical methods in accounting.

“He is a trained accounting historian, but also a theoretician and philosopher of accounting,” said Galassi during his acceptance speech on Mattessich’s behalf. “He regards historical research as no less a search for truth than science.”

During the speech, Galassi quoted an excerpt from Mattessich’s 2000 book, “The Beginnings of Accounting and Accounting Thought,” which he told the audience that Mattessich “would be pleased if these words would be conveyed to the conference participants or an even wider audience:”

Between history and science, there may be important methodological differences (as to generalizability, etc.), but the ultimate goal is surely the same: to approximate what one hopes to be truth, in as rigorous and honest a way, as one is capable of. But no human being can do this without at least some personal judgements. This is precisely why no history or other science can be an individual undertaking; it must be a social enterprise, inculcated with a dialectical process of not merely personal but, above all, a collective soul-searching, constantly adjusting and readjusting for all kinds of biases, be they those of individuals, of fashions, or technical-scientific limitations, etc. Only through such dialectics it is possible to keep one’s bearing on that loft objective which all authentic truth-seekers pursue.